US Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro walks with officials from HD Hyundai Heavy Industries. (Photo courtesy of US Navy.)

Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro has made several speeches calling out contractors for buying back shares instead of investing that money in their facilities. In this new op-ed, Bill Greenwalt of the American Enterprise Institute pushes back at those criticisms.

The US Navy is on the precipice of its greatest crisis in decades as our major shipbuilding programs are wracked by delays while our adversaries’ capabilities continue to grow. Any hope of catching up to China’s massive naval buildup is fading fast, as the inadequacies of peacetime funding and mindsets continue to hollow out our Navy.

Amid these problems, Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro has both the time and the gumption to blast the industry players that enable us to compete. Rather than address our crisis head on and argue for the resources to support the type of naval buildup that is needed, what better strategy than to complain about so-called greedy contractors?

The Navy Secretary has been trying to pin the blame on a profit-seeking industry as the source of his problems. He recently noted that defense contractors are earning “record profits,” while “continu[ing] to goose [their] stock prices through stock buybacks, deferring promised capital investments, and other accounting maneuvers.” He of course included that other bugbear in the anti-industry mantra — executive compensation — as another shot across the bow.

Putting aside the Secretary’s comments about stock buybacks and investments, which Jerry McGinn, Mikhail Grinberg, and Lloyd Everhart have thoroughly addressed, more attention must be paid to the first half of his remarks. The implied conclusion is that the defense industry and specifically naval ship builders are in the midst of an era of grand profiteering and should now do whatever Del Toro says with their “excess” profits to bail him and the Navy out of the tough spot it’s in. If only it were that simple.

It’s unclear exactly what the source of Del Toro’s angst is, but it seems in line with messaging out of the White House. Look at a November 2023 White House Fact Sheet announcing its “Better Contracting Initiative,” which states that “many of the largest Federal contractors [are] operating at historically high margins, resulting in costs to taxpayers that are simply too high.” Citing a study done by Deltek, the White House suggests that “contractor profit margins have grown to 15-17 percent, above historical norms of 6-10 percent.”

But is this true? In other words, is the defense industry really making as much profit as the White House and the Secretary suggest? Examining the profit margins of our top defense firms shows this not to be the case.

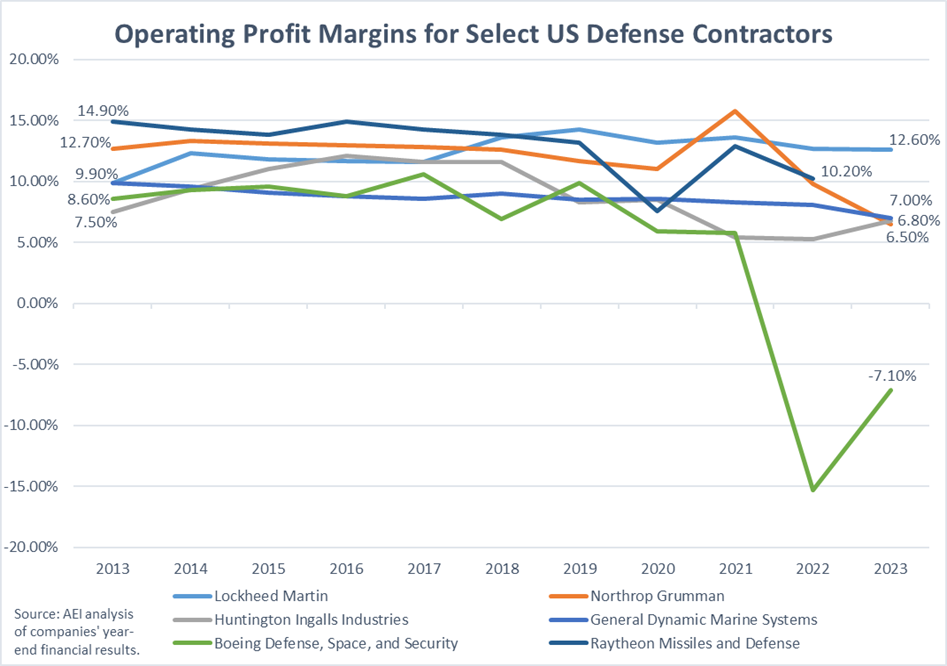

As the below graph shows, for six of the largest US defense contractors that AEI research analysts examined over the last decade, defense-specific operating profit margins are not at all-time highs — and in fact, have largely trended downward in the last ten years, negating Del Toro’s comments. While Lockheed Martin has seen a small upward swing in its trend lines, the other contractors examined have seen the opposite. More specifically, shipbuilding’s margins are approaching the point where investors might do better long-term by starting to think about buying savings bonds. Huntington Ingalls Industries, one of our country’s two major shipyards and presumably a company that Del Toro was referencing in his comments, has seen its profit fall from a decade high in 2016 at 12.1 percent to 6.8 percent last year. The same trend is seen at General Dynamics’ shipbuilding unit where annual profits have fallen from a peak of 9.9 percent in 2013 to 6.5 percent last year. Hardly a record.

This data comports with other findings about profit among defense contractors. Looking at the industry for decades prior to the analysis here, the Defense Business Board showed in 2014 that between 1980 and 2013, the average operating profit margin for the defense industry remained either just above or below 10 percent. In 2023, the average operating margin for the entire defense and aerospace industry came in at 9.7 percent.

In short then, US defense contractors haven’t been reaping record profits, and these have either stayed largely flat or decreased over the last decade.

Compare that to other industries with much higher margins. For instance, green and renewable energy, which is heavily subsidized by the federal government, saw an operating profit margin of 24 percent last year. Should Congress immediately start investigating cases of “green” profiteering? The case can be made for that much more than with the defense industry. Many industries’ comparable profits are even higher. The semiconductor industry, the source of government CHIPS Act giveaways, has profits almost three times (25.28 percent) the defense industry, while software (34.05 percent) is closing in on being four times as profitable. Highly regulated industries like utilities (22.17 percent) and railroads (35.52 percent), and even steel (12.5 percent), in its supposed death throws facing global dumping from China, have higher profits than defense.

How do we explain the White House numbers then? The underlying analysis might have methodological issues in sampling, or mixing apples and oranges by including commercial contractors who will only sell to the government under commercial prices, profits, and terms and conditions. The government may be buying more commercial goods and services and not trying to replicate at ten times the price that which already exists in the marketplace. That could skew the data and see the government paying more in profits to non-defense companies. But buying commercial would be a good thing and has been an objective of acquisition reforms since the 1990s. The other potential explanation to look into is that perhaps some civilian agency contractors may indeed be taking advantage of the government.

The key national security takeaways are that defense contracting profit margins are not even close to being at the White House numbers, are not increasing, and for shipbuilders, are in a freefall decline.

Profit is what encourages companies to invest. If they can’t turn a profit, then there’s little reason to put money into their business, and all of the new technologies, platforms, and weapons that our defense industry turns out wouldn’t come to fruition. The notion that defense profits are at a record high isn’t born out by the data and because of recent declines in these profits we will likely see less outside investment in the sector.

Believing in the falsehood of exorbitant profits in defense as our Navy Secretary advocates skews our collective perception towards our defense industry, making it seem as if it’s practically a government entity and not a group of businesses with their own financial interests.

The Navy needs to relearn that the profit motive and our national defense should go together. It allows our capitalist system to spur innovation in defense, leading to new platforms, new products, and new ways of doing business. Take profit out of the equation and you’d have a military with little innovation, unable to face threats today and badly underprepared for the conflicts of the future.

That, you might note, sounds an awful lot like the situation the Navy is facing today.

William C. Greenwalt is a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a former deputy undersecretary of defense for industrial policy.

Aloha: Fixes ongoing, then Army’s new watercraft prototype is Hawaii bound for testing

“Everything that we can knock off that list we will do in the archipelago…because that allows us to do the tests in the environment that the vessel will operate in ultimately,” said Maj. Gen. Jered Helwig.