A team of Latvian Joint Terminal Attack Controllers participates in an exercise at the Carmeuse Lime and Stone Quarry, Rogers City, Michigan, in 2021, as part of Northern Strike 21-2. (U.S. Air National Guard photo by Airman Katherine M. Jacobus)

In this Q&A with Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, USAF (Ret.), dean of the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, and former deputy chief of staff for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance for the US Air Force, we discuss the future of JADC2 under a new chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the inadequacy of the current defense industrial base; why business standards imposed on the Department of Defense are hindering production; and why jointness is about using the right force in the right place at the right time — not every force, every place, all the time.

BREAKING DEFENSE: You recently sat down with Air Force chief and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs nominee Gen. CQ Brown. How do you think CONOPS like JADC2 and all-domain operations will evolve under the new CJCS once he’s confirmed? What have you seen during his tenure in the Air Force that will likely find its way to the greater DoD?

DEPTULA: Gen. Brown’s very aware of the critical importance of JADC2 and all-domain operations — perhaps more so than any other service chief because he’s actually been a functional joint-force air-component commander in his assignment in the Persian Gulf.

What that means from a mission perspective is it doesn’t matter what service a particular aircraft comes from. It’s the capability that the Air Force aircraft contributes. So it is with all-domain operations and JADC2. His commitment to see these concepts of operation come to fruition are likely what you’ll see him bring to the position as the chairman.

One of the reasons that JADC2 has been languishing, or at least not accelerating as many of us would like to see it develop, is that there has not been a real champion for the concept in the seniormost levels of the Department of Defense. I think Gen. Brown has the opportunity to become that champion.

With respect to what I’ve seen the Air Force do that might find its way to the greater DoD by the virtue of Gen. Brown taking the chairman position, I’d tell you that the next major theater war is going to require a combatant commander to project power and employ combat effects over very long distances. That’s a realization that he may bring to his new job along with the reality, and this is an important one, that the services will not be getting all the resources that each of them requires individually.

Therefore, each of the services need to play to their strengths in order to optimize joint force operations and stop attempting to replicate every function such that they can fight on their own. I think this is where Gen. Brown can really shine as the chairman, and that’s to move the services to focus less on self-sufficiency and more on interdependence.

That’s why I I gave you that perspective on being an actual functional component commander. People who have been combined or joint force air-component commanders truly don’t care about the source of the capability, what’s painted on the side of the airplane. They care about the capability. We’ve never had an airman as a COCOM in Central Command or in Indo-Pacific Command, which is bizarre because if you want to conquer the tyranny of distance in the Pacific Ocean, you do it going 600 miles an hour, not 15 miles an hour in a ship.

Your point about sharing the capability is particularly applicable to accessing data across platforms, services, and partners. How would you characterize the state of this capability today? What has to happen for this capability to break out of demonstrations like the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System into become part of actual warfighting doctrine?

Your question gets to the heart of joint force operations. From a joint force air component perspective, the state of integration of air efforts, in this regard, is outstanding because that’s a function that’s been planned, trained for, and successfully executed since the days of Desert Storm back in 1990/91.

On the other hand, a combatant commander is responsible for the integration of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance across all domains regardless of service or platform of origin. Those that will succeed in this task are those who understand that jointness is about using the right force in the right place at the right time — not every force, every place, all the time, or a predilection for a particular domain or a set of domain-specific capabilities. Frankly, I don’t believe we’re as well off in the combatant commands in this regard as we need to be.

With respect to what’s necessary to break out of demonstrations to become part of an actual warfighting capability, the major challenge today is integrating, fusing, and disseminating a sensor picture appropriate for a particular theater segment accessible at the time of need. To do that requires integration of a huge variety of sensor types and customer requirements across all domains.

That’s not a very easy challenge to resolve, and that’s where a champion for JADC2 at the highest levels of the Department of Defense is required. Someone who is constantly demanding progress in resolving the challenges that are required to achieve the goals and objectives of JADC2. That ultimately is how individual service demonstrations will evolve into actual war fighting reality.

You made the point that all-domain operations don’t have to be happening everywhere all at once. The common picture you described only needs to be appropriate for a particular theater segment. However, that adds another layer of complexity to know exactly where in the world and which theater needs what.

It’s one thing when you put together PowerPoint presentations and [say] we’re going to connect every sensor with every shooter all the time. First, you don’t need to do that. You need to connect the right sensor to the right weapon at the right time in the right place. That’s what’s going to be tough about actualizing this whole notion of Joint All Domain Command and Control. How do you do that?

We’ve got sensor suites that can deliver information globally. But if I am in Theater A, I don’t care about what’s being collected on the other side of the world. Now let’s neck down Theater A. I’m in a sub-segment and got to neck that down to a 10 by 10 nautical square mile container that I’m interested in. The point is, how do you get the people who are responsible on the leading edge of the fight the information that’s necessary for them to optimally employ their weapons with information advantage?

The Mitchell Institute is an “aerospace power” think tank. What does “power” mean in the context of this conversation regarding integrated/interoperable air capabilities?

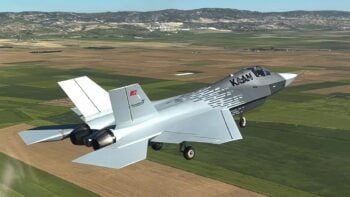

Information is the fundamental basis of power for without data there is no information, and without information there is no knowledge. Accordingly, an F-35 without these elements is just a very expensive, very fast chunk of metal and composites.

Information is the linchpin of successful operations in the 21st Century, particularly since the combat capacity of the Air Force has been slashed to less than half the size it was during our last major regional conflict, the Persian Gulf War. Today the Air Force is the oldest and the smallest it’s ever been in its entire history.

Achieving an information advantage is what our warfighters are counting on to compensate for that deficiency in combat capacity. Achieving an information advantage relative to our adversaries has become an absolute imperative to achieving the power necessary to meet the needs of the national security strategy.

How would you describe the present state of US and allied air forces compared to the day before Russia’s attack on Ukraine? I don’t necessarily mean in aircraft production but in how priorities have changed for future production, fleet mixture, data sharing, etc.

What I’d tell you first is, candidly, the current state of US and allied air forces hasn’t changed much from the day before Russia’s attack on Ukraine. However, what has changed is an increased awareness of the critical importance of air superiority as I described earlier. Because without it, conflicts rapidly devolve into wars of attrition resembling World War I, not the kind of outcomes we saw in Desert Storm.

Second, the war appropriately placed attention on the growth inadequacy of our current defense industrial base to keep pace with modern warfare. We lack sufficient munitions production capacity for sustained conflicts, and that must be corrected. We have to move away from having business standards imposed on the Department of Defense and warfighting because they are two very different models. For example, just-in-time delivery may be a great business model for FedEx, but it’s an absolute disaster waiting to happen for the combatant commanders around the world.

Third, there’s a growing realization that modern warfare will involve attrition to a degree simply not seen since World War II. We need to be prepared for that, both in terms of personnel and equipment on the part of the Air Force. We have to reverse the pilot shortage and we need to correct the capacity deficiency of combat aircraft in the Air Force.

Both of them, by the way, are related. You can’t absorb more pilots without having more capacity in your force to fly them and train them.

Fourth, the importance of logistics. Russia’s failure to supply troops on the ground cost them dearly. NATO and the US are paying close attention to logistics both in the air and over land.

Finally, command and control. The advantages of having a good command-and-control system with an intelligence advantage is huge. It’s part of why the much smaller Ukrainian forces were able to hold off the Russians. We need to accelerate the realization of JADC2 and get it incorporated into our combatant command operations on a daily basis as soon as possible.

In summary, the major effect this war has had on our Air Force is getting the point across that it’s indispensable in executing a zero-fail mission. It shows that future competition with our adversaries is not necessarily going to be limited just to sanctions, trade wars, or low-intensity combat, but will more likely involve major combat operations with existential outcomes for us and our allies.