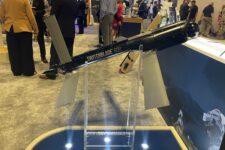

An artist’s impression of the UK-Japanese-Italian Global Combat Air Programme fighter jet (BAE Systems)

SYDNEY — Japan’s cabinet this week decided to broaden its arms export rules to allow sales of the three-nation Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) sixth-generation fighter to any of 15 nations.

The aircraft, jointly developed with the UK and Italy, will only be eligible for sale to countries that have signed agreements with Japan about defense technology transfer. The change had been debated for months inside Japan’s political parties.

“In order to achieve a fighter aircraft that meets the necessary performance, and to avoid jeopardizing the defense of Japan, it is necessary to transfer finished products from Japan to countries other than partner countries,” the Associated Press quoted Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi. “We have clearly demonstrated that we will continue to adhere to our basic philosophy as a peaceful nation.” The cabinet secretary fills a unique role in Japan, coordinating policies and actions across ministries and sometimes speaking for the government.

The decision, clearly taken to ensure that Japan remained a relevant partner in GCAP, may also help defray the enormous costs of developing such an advanced weapon, which can strain even the capacity of the most economically and technologically advanced nations.

The next generation fighter jet is set to replace Japanese F-2 aircraft, alongside British and Italian Eurofighter Typhoon multirole types.

Deterring China is clearly part of Japan’s intent, but countering China’s large numbers of apparently advanced aircraft like the J-20, of which China may have built more than 200, will be difficult. Overall, Japan’s 2023 defense white paper estimates that China has 1,500 fourth-and fifth-generation fighters, greatly outnumbering Japan’s 324.

RELATED: FCAS? SCAF? Tempest? Explaining Europe’s sixth-generation fighter efforts

But will the GCAP jet, set to deploy by 2035, be bought by regional partners to boost that deterrence? Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute says sales will come “down to cost and capability – how much does GCAP cost in terms of both unit cost and sustainment over the life of type.”

The GCAP will be in competition with other advanced fighters, such as the US Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD). “It’s uncertain,” Davis said in an email, “whether the US will export NGAD, so by Japan opening up its options to export, they may (alongside their GCAP partners) be able to tap into a market that the US is unwilling to enter.”

Who might Japan sell GCAP to? “South Korea is unlikely to buy it because KF-21 leads to a future ROK sixth-gen system,” Davis argues. “For Australia, if we can’t get NGAD to replace F-35 then might we look at GCAP? Possibly? But the key issue for Australia is how the crewed-autonomous mix plays out in the next decade with F-35 and MQ-28.”

GCAP and NGAD are both system of system programs, with a highly advanced manned aircraft fighting alongside a fleet of autonomous drones such as Australia’s MQ-28 Ghost Bat.

“Ideally, GCAP or NGAD could operate alongside F-35A and MQ-28 through the 2030s and 40s,” Davis said. “ASEAN air forces? I doubt it, or I doubt they’d be able to afford significant numbers of GCAP platforms.”

ASEAN includes few states likely to spend the high prices required to buy fifth-generation fighters, let alone sixth-generation ones. The most likely state to do so, Singapore, committed to buying eight F-35As this year and has already bought 12 F-35Bs. It also flies F-15s and F-16s. Moving to an aircraft with a substantial quantity of British, Italian and Japanese technology would be a difficult decision to support for a country with an all-American fleet.