Defense Minister Richard Marles at the National Press Club of Australia in Canberra discussing the first National Defense Strategy and attendant Integrated Investment Program.

SYDNEY — The Australian government announced a “historic” shift for the future of the Australian military today, from a disparate force with too many missions to one sharply focused on deterrence and amphibious warfighting in the Indo-Pacific, a force launching new capabilities at sea, on land and the air over the next decade. It’s a strategy that critics argue too little, too late, not boosting spending quickly enough and buying most of its new capabilities more than five years from now.

Key to the new effort, Defense Minister Richard Marles said today in a major speech at the National Press Club in Canberra, will be an increase defense spending by $50.3 billion over the next decade, with the plan being to hit $100 billion by 2033. That would mean Australia would be spending 2.4 percent of GDP within 10 years. He unveiled both Australia’s first National Defence Strategy and attendant Integrated Investment Program more than two years into his government’s tenure.

“Impactful projection through the full spectrum of proportionate response is our task. We must be able to do this in a way which denies any adversary the ability to operate against Australia’s interests: a strategy of denial,” he said in a nationally televised event at the press club. “And building a defense force capable of this is now the Albanese Government’s historic mission.”

Meanwhile, the government also plans to slash some existing programs and redirect that money, including the final squadron of F-35As that Australia had planned to buy, part of a Super Hornet replacement project worth up to $3 billion AUD ($1.9 billion USD).

“So we’ve got 72 Joint Strike Fighters and we’ve got a number of Super Hornets and we’ve decided to keep the Super Hornets in service for two reasons,” Defense Industry Minister Pat Conroy said in an interview with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “One, they’re doing great work. Secondly, the Joint Strike Fighter is even more capable than we initially thought. So we can delay the replacement of the Super Hornet which frees up funding to invest in more long‑range missiles, for example. … This doesn’t mean Australia will totally abjure the purchase.

“So we’re going to continue with the Super Hornets. They complement the Joint Strike Fighter, and we will evaluate possible replacements of them a bit further down the path,” Conroy said.

In response to the cuts, F-35 maker Lockheed Martin told Breaking Defense in a statement that it was “proud to partner with the Royal Australian Air Force to provide the F-35,” which the company said is “driving allied deterrence in the Indo-Pacific theater.” It referred questions about procurement to Canberra.

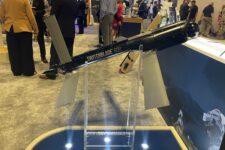

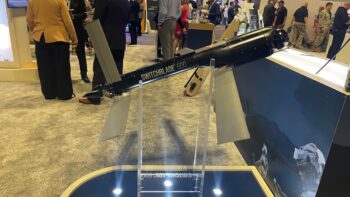

For the broader strategy, Marles and the documents indicated that to improve Australia’s ability to both deter and project power, the government plans to buy new long-range strike missiles, including Tomahawk missiles and spend $28 billion to $35 billion over the next decade.

Chart from Australia’s first National Defense Strategy, outlining planned spending over the next decade. April 17, 2024

The largest chunk of cash in the budget is destined for Australia’s undersea capabilities, according to the investment plan. And while there were scant details specifically about the AUKUS security arrangement, it said the Australian government projects to spend up to $63 billion over the next decade on “conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarines and infrastructure.”

Chart about undersea warfare spending plans in the public version of the Australian Ministry of Defense’s Integrated Investment Plan, released April 17 2024.

The “Unapproved Planned Investment” mentioned in the chart above is money the government allows the Defense Department to plan with, but no money has actually been committed, defense budget expert Marcus Hellyer told Breaking Defense.

In the short term, the government unveiled a plan to invest an additional $5.7 billion over the next four years, with $1 billion of that being for long-range strike, targeting and autonomous systems.

But Hellyer said there’s a catch with the heralded 2.4 percent GDP target: The planned increase — at a rate that happens to also be 2.4 percent — is below the rate of inflation, so in real terms defense is not receiving more money.

“But that’s only a 2.4 percent increase over what was already planned for that period. So, you know, we’re in the worst strategic circumstances since World War II when we’ve got no warning time, and things have even deteriorated. Over a year since the Defense Strategic Review, a 2.4 percent increase seems a little under done,” Hellyer said.

For Robbin Laird, an American defense analyst and Breaking Defense columnist who spent the last few days discussing Australian defense policy and acquisition with senior officials in Canberra, there was little to crow about in the strategy or the plan.

In addition to the shortfall of recruits for the Australian Defense Force (ADF), which Marles said might be met with recruitment from the Pacific Islands and Five Eyes countries, Laird said, “There is real concern in the ADF about a decline in real capability over the three- to five-year period. Over the long term you’re going to get new stuff; over the short term it’s pretty grim,” he said in an interview today. And he pointed to the persistent lack of detail in the ministry documents. “It’s so opaque — what’s the focus really?”

The shadow defense minister, former SAS captain Andrew Hastie, sharply criticized Marles and the government over the strategy, saying Marles used “vague, bureaucratic language in talking about our defense strategy.”

“We are still no clearer on what ‘impactful projection’ is, or how it will work for the ADF,” Hastie said at a press conference following Marles’ speech. “There is a lack of clarity about Labor’s design for the ADF and how the constituent parts will work together.”

Marles did say $72.8 billion would be directed from current plans to other uses over the decade, but neither his speech, the Defense Strategy nor the investment program provided many details about what would actually happen or when.

Some addiitonal details about the cuts to free up spending emerged later in the day. In addiiton to the F-35 slash, the biggest savings came from the reduction in the purchase of the Redback Infantry Fighting Vehicle. Reducing the purchase from Hanwha should free up to $10 billion after the government decided to reduce the purchase from 450 vehicles to 129.

- An ambitious $4 billion maritime mine countermeasure program is axed. The desired capabilities will be replaced by robotics and autonomous systems.

- A $3 billion replacement for Australia’s C-17s known lyrically at AIR 7401 Phase 2 – Heavy Air Mobility Capability, will be shuttered and the requirement for the capability will be considered closer to the aircrafts’ planned replacement.

- A $3 billion project known as AIR 6004 – Air Launched Multi Domain Strike will be closed and its requirements captured in other classified projects.

- An Army project for $2 billion in Individual Combat Equipment Up to $2 billion Project funding focused for priority combat equipment.

- Sky Guardian, the $2 billion MQ-9 program more prosaically known as AIR 7003 Phase 1 – Armed Medium Altitude Long Endurance, Remote Piloted Aerial System, had already been cancelled. Its funding has not moved.

- A $1.5 billion plan to replace the EA-18G is shuttered and requirement will be reexamined closer to the the aircraft’s planned retirement.

- Phase 6 of the plan to upgrade the E-7A Wedgetail will be reduced to provide up to $1.5 billion.

Marles also announced the termination of two Joint Supply Ships for a savings of $4.1 billion. And $1.4 billion in defense infrastructure set to be spent in Canberra will go to bases in Darwin, Townsville and Pyrmont, a suburb of Sydney. In addition, another $2 billion for infrastructure spending will be shifted for work on northern bases.

Hastie cast all those as a budget cut at a time when the government says it faces the most daunting strategic environment since World War II. “Richard Marles has presided over more than $80 billion of cuts and delays to the Defence Budget,” he said.

UPDATED 4/17/2024 at 12:06pm ET to include a statement from Lockheed Martin.