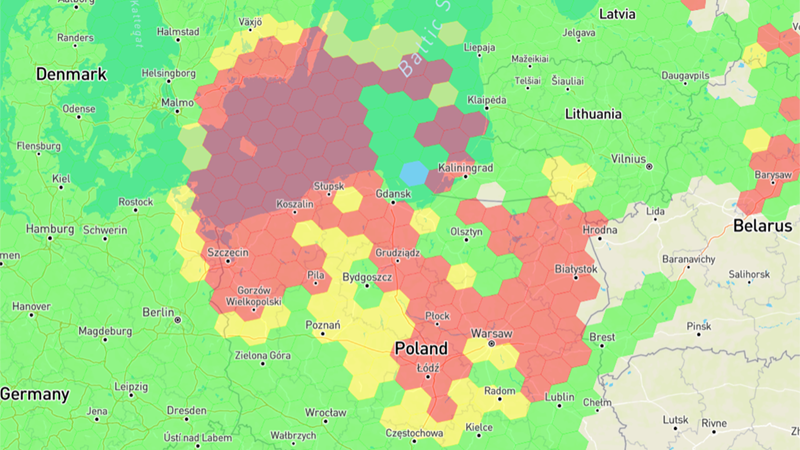

A screengrab of reported navigation issues in the airspace over eastern Europe on Jan. 19, 2023. (GPSJam screengrab)

The war in Ukraine has brought to the forefront new tactics of the modern battlefield, from the use of cheap unmanned aerial vehicles to information war on a scale not seen before. But it’s also been host to the latest in electronic warfare. In this op-ed, Dana Goward, a member of the US Presidents’s National Space-Based Positioning Navigation and Timing National Advisory Board, analyzes what he said appears to be dangerous interference, likely by Russia.

For more than a month, aircraft flying in the Baltic region have been experiencing varying degrees of interference with GPS signals, according to public aircraft tracking databases. In some instances, GPS receivers appear to have been electronically captured, or “spoofed” into showing the aircraft miles off its intended route.

While the jamming and spoofing is hardly new, some level of interference has been evident in the region almost every day, and it has periodically been widespread and significant. Previous reports have identified Russia as almost certainly behind the activity, in support of its invasion of Ukraine and in an effort to harass NATO nations.

Such jamming presents a risk to thousands of commercial aircraft, and as international pressure has so far failed to halt the interference, it’s time for NATO to act — proportionally.

On Dec. 25 and 26 a wide swath of northern Poland and southern Sweden was impacted. The next week, on New Year’s Eve, aircraft across a large area of southeastern Finland reported disruptions. On Jan. 10, 13 and 16 the northern half of Poland was the primary target. On the 19, southern Sweden and northern Poland felt the effects. Estonia and Latvia were the targets most recently on Jan. 24.

In each case the disruption was detected by aviation safety ADS-B systems carried by commercial aircraft, and were displayed on the website GPSJam.org.

Analyses of the Christmas interference by graduate student Zach Clements at the University of Texas Radionavigation Laboratory. Clements studies GPS disruptions and has published on locating the sources from satellites in low earth orbit [PDF].

In an interview, he said he determined a number of transmitters were involved spread across a wide area. Some were simply jamming GPS signals to deny service. But at least one transmitter was spoofing aircraft so their instruments would show them far from their actual location and flying in a circle.

While the phenomenon known as “circle spoofing” has been frequently observed with ships, this was the first time it was reported in aviation.

Clements told me he is reasonably sure the source of the circle spoofing was inside Russia. “The points at which the aircraft began to be impacted by the spoofing and where they regained authentic GPS indicate that the spoofer is somewhere in western Russia,” he said. “Interestingly, the location the aircraft were spoofed to is a field about a kilometer from Russia’s decommissioned Smolensk military airbase.”

Graduate researcher Zixi Liu at Stanford confirmed to me that based on her analysis, a number of jammers were almost certainly involved in the Christmas jamming. Her previous research used aviation ADS-B data to geo-locate sources of GPS disruptions.

Though Moscow has reportedly denied the widespread jamming, Ukrainian media has reported that “…since mid-December 2023, units of the Russian Baltic Fleet have been conducting exercises with the EW [electronic warfare] system Borisoglebsk-2 in the Kaliningrad Oblast.”

Analysts in the US and in Poland told me they believe the interference is part of Russia’s response to increasing western influence near its borders. In mid-December the US and Polish militaries activated an Aegis anti-missile system in the north of Poland. Shortly thereafter, the Turkish parliament began actions to clear the way for Sweden to join NATO, which may explain Stockholm’s troubles.

Such a reaction by Russia would not be unprecedented. In 2022 President Vladimir Putin threatened Finland and Sweden if they sought to join NATO. Subsequently Finnish President Sauli Niinistö met with US President Joe Biden to discuss improving defense ties. Shortly thereafter, planes flying over southern Finland, Kaliningrad, Russia and nearby areas in the Baltic began reporting GPS jamming, according to a report in The Guardian.

The predominant focus on Poland in the recent spate of jamming and spoofing events may be Russia’s effort to downplay the importance of Poland’s new American-made anti-missile system. Similar interference has hampered many of the precision weapons the US has supplied Ukraine. While Poland’s Aegis primarily uses high powered radar, not GPS, the interference could still undermine public confidence in the system.

Some observers have also noted that the interference in Poland has included the road through the strategic Suwałki Gap. This 40-mile-long route in Poland paralleling its border with Lithuania is a direct connection between Russia’s staunch ally Belarus, and Russian Kaliningrad on the Baltic Sea. Military analysts have long considered this area to be critical in any potential European land conflict.

These attacks have targeted the aircraft and vessels of other nations operating in international airspace and waters. They have also impacted the sovereign territory and infrastructure of NATO members.

And they pose a substantial risk to life and property.

“Aviation is always at greater risk when GPS signals are not available or are compromised in some way,” Joe Burns, a senior captain at a major international air carrier told me. Burns is also a member of a board that advises the US government on GPS and related issues. “Interference with GPS increases the risks of accidents and almost always slows the system down, makes flights longer, and more expensive.”

Accidental interference with GPS signals nearly caused the loss of a commercial passenger aircraft in Sun Valley, Idaho in 2019. Aviation interests subsequently cited GPS disruption as an urgent issue to the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). The next year ICAO called upon all nations to note the criticality of the issue and take appropriate actions.

The International Maritime Organization has made a similar appeal.

In addition to being a safety concern, deliberate interference with GPS and other satellite signals is a violation of international law and regulation agreed upon by all member nations at the UN’s International Telecommunications Union (ITU). In a 2022 circular the ITU cited over 10,000 instances of aviation related satnav interference recorded in 2021. The same circular emphasized that such actions violate rules against harmful interference saying “… the use of devices commonly referred as ‘GNSS [Global Navigation Satellite System] jammers’ or any other illegal interfering equipment, which may cause harmful interference to aircraft, are prohibited by provision No. 15.1 of the Radio Regulations …”

The International community must recognize that the kind of electronic warfare being seen in the Baltic is just that — warfare. And, despite not having issued a declaration of war, Russia has deliberately and systematically conducted a series of low-level attacks on others, especially targeting NATO members.

It is also clear that discussions and proclamations by international bodies have not worked. The problem has only worsened.

NATO and the international community have options for appropriate and proportional responses that should be promptly considered and employed. For example, frequency allocations for new satellites are managed by the ITU. Denial of new allocations to nations found to be routinely interfering with signals from other nations’ satellites seems appropriate and could be a good first step.

Regardless of the method, more decisive and overt action must be taken to address this increasing problem before it results in significant loss of life or escalates into armed conflict directly involving NATO.

Dana Goward is the president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation and a member of the US Presidents’s National Space-Based Positioning Navigation and Timing National Advisory Board. He formerly served as the Director of Marine Transportation Systems for the US Coast Guard.

TAI exec claims 20 Turkish KAAN fighters to be delivered in 2028

Temel Kotil, TAI’s general manager, claimed that the domestically-produced Turkish jet will outperform the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.