A J-20 fighter jet of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) performs in the sky during Changchun Air Show at Changchun Dafangshen Airport on August 26, 2022 in Changchun, Jilin Province of China. (Yang Kunye/VCG via Getty Images)

PARIS — The People’s Republic of China’s military aerospace sector has established a pattern of achieving technological milestones — but then keeping completely silent about those advancements during the kind of major international expositions when a newsworthy development is normally announced with great fanfare.

This isn’t just for Western conferences. In the years when it was still safe for western defense correspondents to freely attend the PRC’s largest defense expo, Air Show China, the joke was always that there would be a game of hide-and-seek about news that would only come out after the show. And it seems in 2023, the PRC’s Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) has stuck to the script.

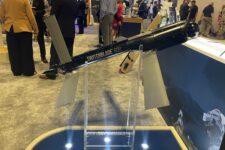

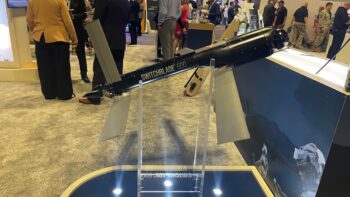

During the week that the world’s aerospace community gathered at the Paris Air Show, no one in the Chinese delegation had any news at all about their most advanced and speculated-about combat aircraft program, the 5-th generation Chengdu J-20 stealth fighter. The only indication that something might be afoot was the subscale model of J-20 on AVIC’s stand in the exhibition hall, one of many models the company showed off at its booth.

But on June 28, four days after the Paris show ended, video emerged of the J-20 making its first public flight equipped with a pair of Xi’an-built Woshan-15 (涡扇-15 or WS-15) “Emei” engines. (While AVIC has not released a statement on the video, the fact it remains up is taken as a sign the firm, and through them Beijing, want the video seen.) While not the first time the WS-15 has been equipped on the jet — it appears to have flown with one WS-15 and one older design in 2022, typical of flight testing for a new engine — the flight with two WS-15s is a sign of maturity and confidence that, after years of delays, a homegrown, advanced fighter jet engine is ready for prime time.

Finally bringing the WS-15 to successful operational status is a major milestone for Chinese aerospace. That the PLAAF now have an engine that delivers the range/payload performance that the J-20 was designed for from the beginning makes the fighter jet more of a concern for the US Navy and other US partner nations in the Pacific that could potentially encounter it in combat. The system should provide a significant boost in performance over the previous engines used by the J-20, the Russian Salyut/Lyulka AL-31FN and the successive WS-10 variants built by the Shenyang Liming Aircraft Engine Company.

“No one wants the Chinese to become capable of designing and building their own jet engines,” said a retired NATO-nation intelligence officer who spoke to Breaking Defense. “It would move the threat marker as to their air power capability up more than just a couple of notches. But they seem to be close to that goal whether we want them to be or not.”

A Long Developmental Goal

Development of jet engine designs by PRC industry in general and the WS-15 in particular is a goal that has eluded the Chinese for three decades. AVIC’s military aircraft programs have had to rely almost exclusively on jet engines produced by and imported from Russia.

Both the J-20 and the Chengdu design team’s previous-generation fighter model, the J-10, were initially powered by the Salyut/Lyulka AL-31FN. The JF-17 fighter aircraft designed for and jointly manufactured in Pakistan is equipped with one of the Mikoyan MiG-29’s Klimov/Isotov RD-33, re-designated the RD-93 in this single-engine installation. (Two of these engines also ended up being utilized for prototypes seen in 2014 of the Shenyang FC-31 fighter, that in its current iteration is expected to become the PLAN’s next carrier fighter.)

As the J-20 program progressed it appears the Chinese realized that the WS-15 would not be ready for initial production batches of the aircraft. This prompted the Chinese in 2010 to request the purchase of a large number of the Saturn/Lyulka 117S/AL-41F-series jet engines from Moscow.

This model had been previously described to Breaking Defense by the Saturn design team in Russia as a “deep modernization” of the AL-31F-series power plant. This modernized design currently powers the Sukhoi Su-35S and also the initial production runs of the 5th generation Su-57.

Moscow turned the Chinese down, telling them the only path to gain access to the engine’s design and the technology was to purchase the Su-35S export model, a process of negotiations that dragged on for another five years. When the deal was finally signed in November 2015 it was for 24 Su-35S aircraft to be delivered to the PLAAF at a cost of over $2 billion.

RELATED: China should ‘worry’ about Taiwan 2027 timeline, J-20 is just ‘OK’ fighter: PACAF chief

Breaking Defense spoke to representatives of Sukhoi after deliveries had begun and asked how many spare engines the PLAAF would be receiving with each aircraft. “It depends on the customer,” the representatives said at the time, without being specific. “Some customers will purchase two spare engines with each aircraft, some will take four — and customers with a lot of money — well, they will buy eight spare engines per aircraft.” The implication was that this latter option was what the Chinese decided on.

It was around this time the PRC’s defense procurement planners came to the conclusion that their industry’s inability to design reliable and effective fighter jet engines had to be addressed. In August 2016 it was announced the various jet engine industry component units within AVIC would be consolidated into a new standalone entity — the AeroEngine Corporation of China (AECC) — and would form a new company worth $7.5 billion in registered capital, employing 96,000 personnel.

The company took on several ambitious projects, of which WS-15 was only one, but had difficult going in the beginning. Two years after AECC’s formation the company was preparing to display the engine at Air Show China 2018, only to cancel its appearance when a WS-15 exploded during a test run on a ground station just prior to the expo — repeating a similar failed test in 2015.

But development continued, culminating in the flight test two weeks ago — a potential milestone for China’s military engines.

A model of the Chengdu J-20, produced by China’s AVIC, is seen at the 2023 Paris Air Show. Chinese military firms had a sizeable presence on the show floor. (Aaron Mehta/Breaking Defense)

What The J-20’s New Engine Means

The June 28 flight of J-20B (the designation when fitted with two WS-15 engines) appears to be the first time the aircraft has flown with the new engine in both nacelles. Standard practice in evaluating a new engine design in a twin-engine fighter has been to begin flight testing with one new engine in one nacelle and an older-model engine in the other in case of a failure.

A Chinese military think-tank researcher described the significance of this WS-15 test flight to the English-language Hong Kong South China Morning Post, saying “after 12 years since the J-20’s maiden flight in 2011, the Chinese air force finally got the engine it had long been waiting for.”

The series of Chinese-built engines that have powered different production batches of the J-20 have incrementally increased the performance of the aircraft. Thrust-to-weight ratio of the original WS-10 engine model was 7.5, the improved thrust variant, the WS-10B is rated at close to 9.0, with the WS-10C performing at 9.5 or better — enough for the J-20 to be capable of supercruise.

The thrust-to-weight ratio of the WS-15 Emei engine is supposedly greater than 10, which puts it near the performance of the F-22A’s F119 engine. But a former PLA instructor, Song Zhongping, who also spoke to the SCMP, stated the WS-15 did not yet have the endurance of American engine designs.

“There is still a gap between WS-15 and the F119 engines,” he explained. “It’s an experimental success for the WS-15, but it’s too early for it to enter mass production. It still needs tests and improvements.” Among these: the engines seen so far in photos released of the June 28 flight appear to lack the thrust vectoring control module that the aircraft’s operational specifications call for.

The engine’s reliability, MTBF and other parameters are most likely inferior to any western design, but unless exports to the PRC of some of the world’s most sophisticated, 5-axis and 7-axis machine tools are curtailed those shortcomings will also disappear over time.

At Le Bourget this year, officials from the Ukraine aeroengine firm Motor Sich and the co-located design bureau Ivchenko/Progress complained that in past years, the US Government had been in constant contact with them over the issue that they not sell out to Chinese ownership. Washington did not want Ukraine’s expertise in engine design to fall into Beijing’s hands. Now, they claimed, they have almost no interaction with the US Government or its major defense contractors, despite their efforts to re-open the dialogue.

Which comes back to the question of why the Chinese waited this long to make the announcement, rather than score a big media coup at Le Bourget, with the world assembled.

“The Chinese never coming clean about what they have planned for one of their newest and most advanced programs seems at odds with the common sense of wanting to use an event like Le Bourget to maximize publicity – as most western companies do,” said a retired western military intelligence officer and experienced China analyst.

“On the other hand, by waiting a bit and making these announcements on a date of their choosing they fulfil the traditional Chinese objectives of controlling the narrative on their terms. Most important of all — they end up having the world’s stage all to themselves.”