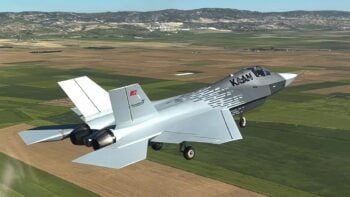

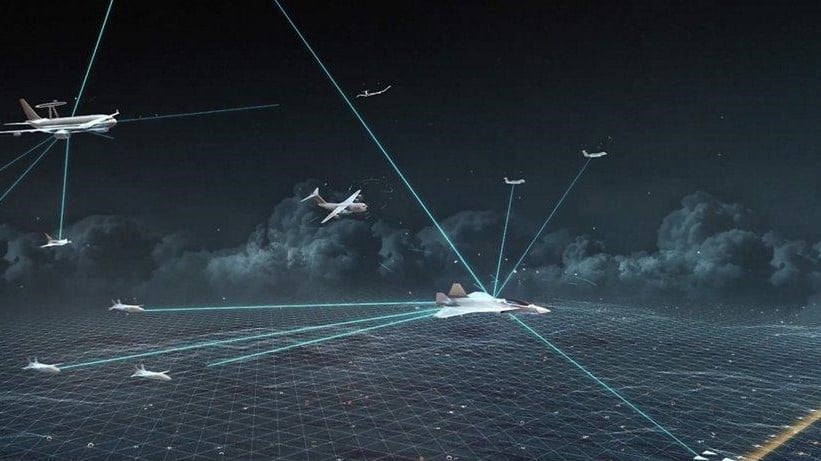

Airbus graphic of its nominal FCAS concept. (Airbus)

PARIS — France’s Dassault Aviation and Germany’s Airbus Defence & Space might be close to resolving their differences about workshare on the Next Generation Fighter (NGF), the 6th generation fighter at the heart of the Franco-German-Spanish Future Combat Air System — but ironing out the business issues now seems to have pushed the operational date back by several years.

“We’re not far, but not there yet,” Dassault’s CEO Eric Trappier told media on July 20 in Paris, just before the European defense community’s traditional vacation period of August. Originally planned to replace the French Rafale and German and Spanish Eurofighters by 2040, Trappier says that “with the delays it’s already too late for 2040. We’re more likely headed for the 2050s.”

The program, now known by its French acronym SCAF to differentiate it from the British-Italian FCAS program, will operate in a network with remotely piloted air systems, known in this program as unmanned remote carriers/Loyal Wingman, with Airbus as the prime for the unmanned portion. Spain’s Indra is the lead contractor responsible for the sensors, alongside Thales and Germany’s FCMS.

As with other sixth-generation fighter designs, tradeoffs are going to define what the jet ultimately looks like. NGF must find a balance between high stealth capability and the best aerodynamics and between measures to locate a target and countermeasures to protect the aircraft from being detected. It will need to carry high precision air-to-ground and long-range air-to-air weapons. It will need enough computing power to process huge amounts of data resulting from operating in a network, but will also need powerful protection from opposing electronic measures and cyber attacks.

But before any technical decisions can get finalized, the companies need to figure out how to “reach an agreement that satisfies the interests of all three nations in terms of participation on an equal footing,” as a German Defense Ministry report wrote in June.

“This program is, by essence, extremely complicated,” said a French defense expert, who spoke on condition he not be named. “And it’s behind schedule not only because the German bundestag [parliament] has to vote for every defense procurement but also because the three partners are bickering over who gets to do what.”

Dassault is the prime on the program, with Airbus its main partner — but the two have openly disagreed on what a prime’s responsibilities are in the program. “We think that in order to build a demonstrator, the company that designs the aircraft is also the one that should design the flight controls. And that’s Dassault,” Trappier explained in March during the company’s annual results press conference. In July he followed up by saying “we are simply asking the Germans to have confidence in our leadership… Airbus is the strong prime on Eurodrone and we don’t have a problem with that. We are simply asking for reciprocity (…) and the day we have that there will be no problem.”

RELATED: Italy expects Tempest exports by 2040; Japan working on jet’s Jaguar system

Michael Schoellhorn, the chief executive of Airbus Defence and Space, is Trappier’s key interlocutor at Airbus rather than Guillaume Faury, the Airbus CEO. Schoellhorn said in an interview with French business daily Les Echos in June that “there is indeed a difference of interpretation between us and Dassault on how to carry out real industrial cooperation. Our disagreement relates more particularly to the sharing of tasks on the flight controls and stealth. If the prime contractor Dassault wishes to manage these two key areas of stealth and flight controls without consulting us, then no.”

He stressed that “Airbus is not Dassault’s supplier on this aircraft. We are the main partner.” And he added that when Dassault declares itself to be the “’best athlete’ by asserting that we, Airbus, know nothing about the flight controls of fighter planes that is not only untrue but contributes to undermining the spirit of cooperation and mutual respect.”

For Jean-Pierre Maulny, deputy director of the Paris-based Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques (Institute of International and Strategic Relations) “it’s extremely difficult to know where the SCAF negotiations stand but I have the impression the French government doesn’t want to put pressure on industry. This procrastination has to stop and some hard punches thrown. It’s up to [President Emmanuel] Macron and [Chancellor Olaf] Scholz.”

F-35, FCAS Impact

Whatever the SCAF’s problems might be, they are not directly linked to Germany’s decision to procure F-35s from the United States according to the French and German researchers and analysts that Breaking Defense spoke to.

Christian Mölling, research director at the Berlin-based Deutsche Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik (German Council on Foreign Relations) who specializes in security and defense, stressed that Germany “has always argued that the F-35 and SCAF don’t interfere with each other,” adding that Berlin is hoping participation in the SCAF program will improve its know-how in certain areas of technology. “With the introduction of FCAS, Germany will be able to make qualitatively and quantitatively decisive contributions to offensive and defensive air operations from 2040+,” the German Defense Ministry report notes.

“France and Germany’s past attempts at cooperation on defense projects have been fraught,” the French defense expert said; Mölling, for his part, pointed to Germany and France’s failed previous attempts at developing a joint combat aircraft: Tornado was jointly developed in the 1970s by Italy, Britain and West Germany and then the same three, joined by Spain, developed the Eurofighter Typhoon in the 1990s. “We don’t need the F-35 to kill SCAF,” he laughed.

Maulny, who co-authored a paper with Mölling in January 2020 called “Consent, Dissent, Misunderstandings: the problem landscape of Franco-German defense industrial cooperation” laughed when told of Mölling’s comments, saying “for once there is Franco-German agreement! I couldn’t agree more with Christian that we don’t need the Americans to sink SCAF.” But he pointed out that for the moment “the Germans have split the difference: they’re buying American with the F-35 but European with the Eurofighters.”

The F-35s will allow the German Air Force to continue its nuclear participation in NATO by carrying US nuclear bombs stored in Germany. The 15 new Eurofighters will be dedicated to electronic warfare.

If the SCAF program goes belly up or “becomes too expensive we can always join FCAS,” Mölling said, adding that “Germany would always officially deny” this Plan B.

The French defense expert countered that the rival British-Italian FCAS project for a 6th generation fighter is “a shadow program,” now also facing some headwinds following Sweden’s decision to, as Saab president and CEO Mikael Johansson put it Aug. 26, “take a back seat.”

“We are on the margins, and our involvement has not been as intensive as we thought at first,” Johansson said, explaining that Sweden has not exited the program “but there is a hibernation period for Sweden while we see the UK, Italy and potentially Japan set up a program. I’m not sure how it’s going to play out.”

For Mölling, the future of both these European programs lies in German hands. “The baseline for both SCAF and FCAS is that nobody has the money except for Germany.” And for the French expert “the Germans have the money but don’t know what to spend it on. It’s a bit like when it rains heavily on ground that is suffering from drought: it’s so dry it cannot absorb all the water.”