Col. Richard Wright prepares to take aim at an unmanned aerial system remotely controlled by as Command Sgt. Maj. Wilfredo Suarez, August 20, 2018, at Combined Task Force Defender. (Capt. Marion Jo Nederhoed/US Army)

WASHINGTON — US Army leaders call them the new “improvised explosive devices.”

Small drones, flying above military bases or personnel in the field, packed with explosives can be delivered on targets with lethal effects at minimal cost to the enemy. And as drone technology continues to evolve, US military leaders expect they will attack on the battlefield in swarms, operating with autonomous capabilities that will make them more difficult to knock out of the sky with the jamming technology largely employed to counter drones today.

“The autonomy is a direct attempt to evade the EW type of capability,” Maj. Gen. Sean Gainey, director of the Pentagon’s Joint Counter-Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Office and the Army’s director of fires, told Breaking Defense in an interview last month. “There are still some ways in EW capability that can still get after some of this threat, but you’re going to start leaning more towards having a kinetic solution.”

So as the Army forges ahead with its drone defenses, its current strategy to defending installations and personnel from small drones is a “layered approach,” in which capabilities work together in a system of systems to detect, track and defeat drone threats — while working at various ranges.

The Army is going to “the kinetic pendulum against this threat,“ Gainey said. “That’s the beauty of having a range of effectors inside of your system of systems approach.”

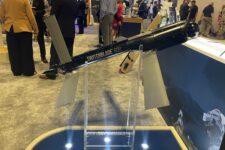

Through a series of semi-annual experiments in Arizona, the Army, the designated executive agent for the joint force for cUAS, has tested a variety of counter-drone solutions at differing ranges, including bullets, electronic warfare, drone killing drones and directed energy to counter small flying threats. As part of a layered defense, these systems would work in combination with each other to defeat drone threats.

“Anyone who’s serious about the drone threat knows that it’s a combination of solutions. It has to be a layered solution,” said John McCollum, a Northrop Grumman business development director, during a recent media event. “It probably is an answer of ‘yes, we need many of these things.’”

But as drone threats continue to evolve, more automation and drone swarms force will force the US and its industrial partners to develop new systems to defend soldiers from the increasingly capable swarm. Add in the burgeoning field of loitering munitions, and the threat becomes more complex.

“It probably moves us the direction we’re already moving anyway, which is … not just shooting projectiles at it, but electromagnetic pulse or lasers or some other way of bringing down the drone,” said Bill Lynn, Leonardo DRS CEO, told Breaking Defense in a July interview.

Layers to defeat evolving threats

Of all the concerns the cUAS community has to deal with, it’s the idea of widespread automation that seems to be the biggest concern.

“It [the autonomy] means that all the SIGINT sensors in the jammer will be less effective than today,” Meir Ben Shaya, senior director of business development for air and missile defense at Rafael, said in an interview earlier this summer. “This is the reason that we need, first of all, to establish a capability of hardkill like a laser, and we believe that the laser will be the future. This will be the backbone of the future solution against the drones.”

Lasers, and directed energy systems more broadly, are already part of the Army’s plans for cUAS. The service’s 35 modernization programs includes two directed energy systems, Indirect Fires Protection Capability-High Energy Laser and Directed Energy Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense, with additional plans to mount a laser weapon on an infantry squad vehicle.

Directed energy systems will be an important part of the service’s counter-drone future, in part because inexpensive smaller UASes cause a tricky dilemma, particularly if they are equipped with explosives. As Gainey points out, those drones may be equipped with an explosives, and knocking it out of the sky with an EW capability could drop an explosive drone dangerously close to soldiers.

“You want to make sure, in this layered approach, you’re able to affect it out as far as you can, without waiting [for] it to get too close to you,” Gainey said.

“That’s why I’m a big fan of directed energy also,” he continued. “We’re having a lot of success with directed energy going after the smaller UASes. So as we’re able to scale directed energy and at the right wattage — because depending on the wattage you’ll probably be able to put effects on it further and quicker — all of these low cost-type, kinetic solutions play into it when you go after the smaller UASes.”

During the Army’s semiannual experimentation at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz., it’s tested counter-drone capabilities against air platforms of various sizes. During its most recent experiment in April, Leonardo DRS, Raytheon and Epirus tackled a “swarm” of two drones at a time, using high-power microwave capabilities.

As drone swarms grow in size, developing a layered defense is critical, according to Leigh Madden, CEO of Epirus, which makes high-power microwave (HPM) weapons. For example, he said, the probability of defeating a swarm of 1,000 drones is higher — and more affordable — if HPM is paired with, say, a .50 caliber machine gun, instead of the gun shooting enough rounds into the sky to defeat a giant swarm.

“If I can put .50 cal rounds in the air and put high-power microwave in the air, I’m going to feel a lot [more] comfortable that any single drone that might slip through one will be taken out by the other,” Madden said. “So that’s how I think about the layer defense, is that you want to increase your probability of kill … And if you’re using multiple technologies to do that, your chances are always improved.”

Experts did add that EW solutions won’t become completely irrelevant. In the future, some drones will still have an electronic signature, navigational link vulnerabilities, or communications link back to a controller that can be jammed, said John Baylouny, chief operating officer at Leonardo DRS. Those electronic attack capabilities would just have to be part of the system of systems approach.”

“We have to plan in our planning for multiple modalities, not just to detect but also to defeat. So this is part of all of the systems that we’re designing now will have multiple modalities — not just the electronic warfare, but also kinetic and possibly even directed energy,” Baylouny said.

“So we have to think about all possibilities because today’s drones are yesterday’s IEDs, right? We expect them to evolve.”

Aaron Mehta contributed to this report.